The Paleolithic Hermeneutic

One of the things that I love to do when I come into new, potentially paradigm-shifting information, is to just think about the ramifications if this idea is true. A kind of Einstein-inspired sitzdenk.

What follows are some thoughts I’ve had about what anthropology seems to be saying about our earliest ancestors and how that helps us interpret human nature and religion.

It is so hard for us in the 21st century to truly understand the headspace of our earliest ancestors — both anatomically modern humans and earlier hominids. They are like us and yet not like us.

Fortunately, thanks to what we’ve learned from anthropologists mapping the most ancient of still practicing hunter-gathers and what we know about our history since the dawn of agriculture, we can infer a great deal.

For one, humanity was very spread out in the earliest times. The largest social units were bands of people of no more than 50 to 100 people.

For another, there were really no leaders. Elders were respected, but not ‘in charge’ as we think of it today. When everything you own comes from Nature and your possessions are only what you can carry, what does it mean to be in charge?

In direct opposition to our modern notions of private property and hierarchy, early humans needed to co-operate with each other to survive, because there were plenty of predators to pick off a single human alone. Exile meant death, and co-operation meant survival.

As a consequence of this, so this view says, there was greater equality between men and women. Yes, there were definite gender roles, but in terms of decision making and especially in terms of sexual access, the best evidence seems to be showing that the Neolithic — post hunter gather — idea of marriage did not exist.

In fact, sex seems to have been viewed just like any other commodity in those times — a resource to be shared and not fought over so as to protect the social bond that kept everyone alive.

We can find supporting evidence for this hypothesis by looking at the studies of hunter-gather societies since the start of anthropology.

In many such societies, the question of paternity is not important, and indeed all the men of the tribe take a role in providing and caring for all of the children. I suppose when any child in the village could be yours, it makes sense.

This sort of free attitude to sex is also attested to by looking at our closest living relatives — not chimpanzees but bonobos. Bonobos use sex to diffuse tension and build social bonds and also interestingly, freely choose to engage in sexual activities with members of their own sex.

Interestingly, this telling of our earliest history completely flies in the face of Darwin’s view of human sexuality. Where in a female has to be choosey because she can’t support a child on her own, and men compete with each over resources so as to prove they are the best mate.

This hypothesis has completely lost the argument as it concerns most of human evolution. It turns out that hunter-gather societies are remarkably carefree, especially in temperate climates in which we evolved.

It turns out that most ancient peoples spent less than 20 hours a week procuring food, and a given the sharing nature of early humans, having a child and not knowing who the father was didn’t spell economic doom.

This was because women could gather and hunt small game for themselves and their children, and as mentioned before all resources in the group were shared.

This all changed 10,000 years ago when agriculture was developed. Suddenly, where before women had equality with men and had a child on average every 4 years, the demands of producing agriculture forced women into a secondary role in producing food.

That coupled with an increased food supply and no need to wait until a child could walk before having another, suddenly women could produce more children, on average every one every 2 years.

The increase of population led to specialization and more importantly, to the idea of private property. When all your needs are provided from a seemingly unlimited nature, it doesn’t make sense to fight and risk injury and death over what is free.

And in the beginning, the first agriculturalist probably didn’t fight either. However, as the famous story of Abraham and Lot indicate, even 3000 years ago, the land was not infinite. And definitely not the most fertile land.

As land started getting scarce, it eventually lead to widespread polygamy and limited monogamy, and later during the Roman empire, widespread monogamy and limited polygamy.

So why exactly did this happen? Well, the consensus is that it, in the beginning, it was because men wanted to be sure the children they were passing their land to were, in fact, theirs and not some other man’s.

While I think there must have been an initial incentive for women to assent to this, over time, it stopped being a discussion, and women also became objects of property.

But like anything, over time, culture and religion created justifications for this and it simply became the ‘natural’ order of things.

And from there, patriarchal society grew and evolved and war and oppression became a reality. In a way, this picture mirrors what the Bible says about a carefree existence at the dawn of humankind, and then a fall from grace.

So that is the overview of what our best research, along with some pop science, seems to be telling us. What does this have to do with religion? Everything.

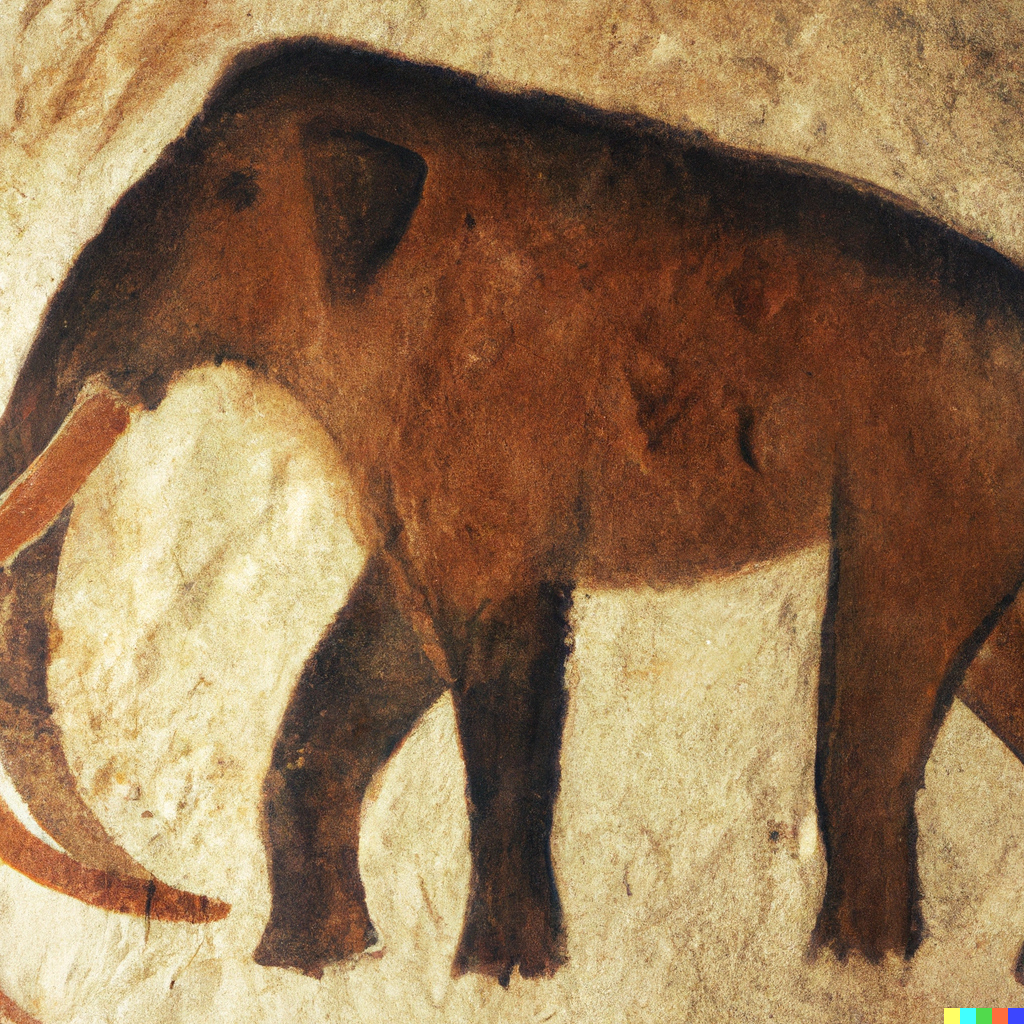

When I first started learning about these ideas, I also looked into early spiritual and religious practices. While varied, I think it is safe to say that early humans spirituality were usually animistic in nature (pun intended).

Animism is simply the belief that there is a life force, a spirit, in many things that are alive, and some that aren’t like a mountain or river. In Europe, for example, there was a very widespread cult of the bear which later included many rituals surrounding the bear.

Notice for a moment, that animism, fits perfectly into the world that our earliest ancestors lived in. A communal, sharing culture juxtaposed against a very harsh and unforgiving world.

People would pray and give thanks to the spirits which sustained them and firmly viewed themselves as a part of Nature, not separate from it.

As far as I know, there is nothing in pure animism that invokes a hierarchy and certainly not a creator God who hands down laws pertaining to sacrifices.

But as agriculture took hold and tribes and later nations developed, you see polytheism start to be practiced.

It is curious that in many of the polytheistic cultures there are some gods which are synonymous with aspects of nature and there were other gods with more urban characteristics.

For example, in Greek Mythology, there is Poseidon who represented the vast untamable energy of the ocean. Then you had Haphestus, who was for all intents a glorified tool maker. Poseiden is clearly a holdover from animistic times.

Then around 3500 years ago, you start seeing even more hierarchy in the pantheon of deities, and henotheism began. Henotheism is the belief in many God’s, but a belief in one “most high” god that is in charge of them all.

This is the stage of religion that we see unfolding in the oldest parts of the Bible. A strong argument can be made that Abraham worshiped El, the most high god of the Canaanite pantheon.

Later on, Yahweh appears, and takes on attributes of both El and his son Ba’al and declares that he is the most high god.

This evolution in the concept of their God, explains why many Israelites felt no shame in worshiping other Canaanite deities such as Asherah, Ba’al, and others.

In fact, it wasn’t until the defeat of the northern kingdom, and the reign of King Josiah, that Yahweh, backed by political power, ascended to be worshiped only.

Furthermore, it’s only when the kingdom of Judah is defeated and taken captive to Babylon, that we see the idea of strict monotheism take hold.

What’s the point of going over this?

I think that there is a strong, almost undeniable correlation, between the political structure of a society and their religion.

Seen in this light, the Bible comes to life. The people who wrote the Bible were 6000 years in on the agricultural revolution. Private property and war was just how life had always been.

The status of women (and other people) as property was also a given. It is why many of the patriarchs and kings had multiple wives, and why according to the Law of Moses, a father could sell his daughter into slavery or a rape victim was forced to marry her rapist.

Add to that a power-based hierarchy, is it any wonder why the early Israelites conceived of God as a fearful king who does what he wants? And as a lawgiver whose laws must be obeyed, even if it meant killing other people and taking their stuff?

It also explains why adultery was such a huge deal back then. It wasn’t a betrayal of the heart as much as the wallet.

As mentioned, both men and women could become objects owned by other people. And demonizing lust, a fundamental part of human nature, was really to protect property.

It’s also why in Greek and Roman culture there were no lines of heterosexual or homosexual. Rather it was about dominance. A free-born male could do as he wishes with whoever, but to submit to the advances of another was considered shameful.

Property. Power. Politics. It is the blessing and curse of the agricultural revolution.

Ever since I started looking seriously at my Christian faith, I’ve been deeply disturbed by how cruel and barbaric the Old Testament is. And while many Christians may be content that it was only for a time until Jesus arrived, I don’t buy that.

Observed through the lens of the Paleolithic, which was 10 times longer than the Neolithic, the Bible, and indeed many other religion’s sacred texts were written by Neolithic people and pertained to the needs, wants, and ideas of their time.

It is telling that in many ways, we moderns have superseded the morality of that time. I would hope that all of us no longer support slavery and the oppression of any group of people.

In short, this view of humanity’s origins is a powerful critique of dogma and a great hermeneutic to read the Bible through.

So then, what does this mean for those who would call themselves Bible-believing Christians, Jews, or whatever?

First, it means that we have to stop pretending that the Bible is this perfect document dropped out of heaven without any problems in it whatsoever.

It is a collection of books, that over time, document moral progress as God steadily unfolds his plans and purposes.

Many people want to judge the Bible for not being ahead of the times. For not taking an ethical standard that we would recognize as enlightened today.

But in many ways, there were enlightened ideas in the Bible — for their time. The laws concerning the treatment of female prisoners of war, or the limits on the slavery of countrymen, were a small, but significant step in the right direction.

But we can’t whitewash the Bible and pretend like bad things aren’t there. That means, we have to accept that to whatever degree God inspired the Bible, he did so in the context of their culture and human nature. Even the evil side of human nature.

Personally, I can’t think of a greater example of incarnational theology, other than Jesus of course, than to see the hand of God at work throughout the Bible moving the needle forward on social progress.

Second, it means that we have to stop looking at the Bible as a systematic theology. It’s just not.

We have to stop thinking that the Bible explains everything we need to know or could know about God. It reflects the nature of God in many places, but also it often simply reflects the ideas of the people of the time. I won’t even get into talking about a 3-tiered universe!

Third, we need to stop demonizing basic human nature. Yes, I’m talking about sexuality and sexual desire. Realizing that we evolved with pretty much no restraints on our sexuality except what our tribe (not God) allowed, we should stop feeling guilty over natural sexual desires.

If there is a fight between religion-based morality and biology, I’m going to bet on biology every time because that is how we are made.

That said, having desires is one thing, and how you act on them is an entirely different thing. Having desires is normal, even if they are kinky. But how you act in response to those desires determine if your actions are good or evil.

In closing, I’m always a bit of a skeptic on how things were in the past, but I think this view of history has a lot of weight behind it, and if it is true, there are a lot of things we have to grieve over and a lot of things to celebrate.

We live in the modern world and our challenge is to find a way to take the best of the Paleolithic — a communal sharing culture, a love for nature — and integrate it with the world we live in a way that respects and protects every member of our society.